Like everybody else, I’ve been diving into the Generative AI (GenAI) hype. Not just to use it, but also to understand how the most popular GenAI products work under the hood. One term gaining recent popularity is Retrieval-Augmented Generation, or RAG. This sounds impressive and complex, but I’ve found it is actually not a difficult concept to grasp or even implement. In this article I will explain RAG in simple terms.

We will cover the three components commonly used for retrieval-augmented generation:

- Large Language Models (LLMs)

- Context

- Vector databases

When we’re done, you will see that RAG is really nothing more than saying: hey LLM, here is a bunch of data, can you tell me <X> about it?

Large Language Models (LLMs)

LLMs are the foundation of the current wave of AI products and services. These giant ML models are trained on enormous sets of data. For example, the Falcon 180B model was trained on 3.5 trillion tokens (a token is generally a representation of a word or subword in a body of text). Training an LLM typically takes weeks or months of continuous large-scale calculations. The hardware and energy cost required to train these models make developing LLMs prohibitively expensive for all but a few companies – like Meta, Google, Amazon, and Microsoft.

LLMs are trained on a very large amount of publicly available data, allowing them to answer questions about a broad range of subjects. However, they know nothing about private data. If I would ask them what I ate last week, for example, it would not be able to answer it.

Because of the training cost and time it would be infeasible to retrain an LLM with my dinner history included. Yet I might like it to suggest a new meal based on the things I ate last week. So we need another solution.

Context

When comparing LLMs, one term you’ll often see is context window. For example, Amazon Titan has a context window of 8k tokens, GPT-3.5 has a 16k window, GPT-4 has a 32k window, and Claude 2 goes up to 100k tokens, and there are models with even larger context windows. The context window defines how much data you can feed a model when asking a question. So on Amazon Titan, you can roughly send a question of 8000 words.

Most of the time a question is only a couple of dozen words, so we can use this context for other uses. For example, we can use it to feed the model additional data. This might sound complex, but the actual implementation is extremely simple. The easiest way to provide additional data is by prepending it to the question. We can use a template to do this:

SYSTEM MESSAGE: You are a helpful AI which helps the user decide what to cook next. The user will provide a list of recent meals, and you will suggest a new meal that is like the others.

CONTEXT: These are the user's most recent meals:

{context}

QUESTION: Please suggest a new meal based on the recent meals above.Now we just need to replace {context} with a list of meals, and we’re done. No retraining of the model needed.

Embeddings and vector databases

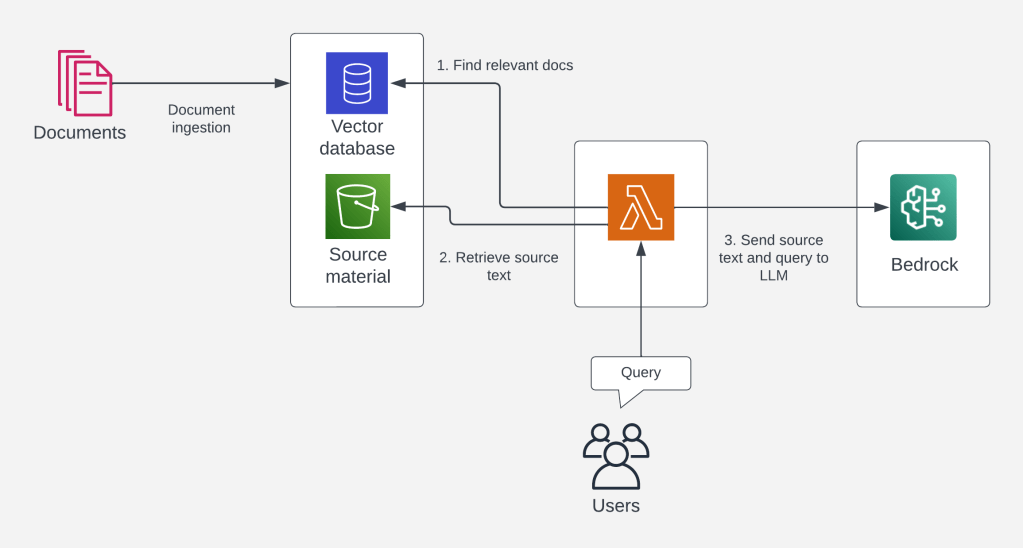

With the enriched context covered above, we could say we have achieved “augmented generation”. The part we haven’t covered yet is retrieval. In the suggest-a-dinner example we could simply read the last few entries from a journal, spreadsheet, or wherever you keep track of what you eat. In many cases, however, you do not know which data to send to the model, or where to find it.

A commonly used example is private corporate data, like an internal wiki or knowledge base. This wealth of data will always be larger than 8000 words in size, so you can’t load the entire knowledge base into the context window. You could theoretically use a model with a larger context window, but these are much more expensive to run. Additionally, very large context windows lead to certain quality / accuracy issues. Instead of loading the entire corpus into a context window, we’re better off providing only the most relevant data to the model. This raises the question: how do we find the most relevant data? The answer: with vector databases.

This is the most complex topic in this article, but I’ll try to keep it as simple as possible. If you have a large body of text, finding certain content in it is a hard problem. You could scan every word and return the matching results, but this would be very slow and error-prone. You might search for the word “cat”, for example, but the document you’re searching for uses “feline”.

The modern approach is to convert a text to “embeddings”: numeric representations of the text, where closely related words (like cat and feline) have a closely matching value. These numeric values (vectors) can be efficiently searched and compared, allowing a vector database to easily retrieve texts matching a given search query. This is also why vector databases are commonly referred to as vector indices. They are literally an index of your source material, stored as vectors.

So a vector database allows you to find the texts most likely to contain the answer to your question. You might type “what is the average weight of a American Shorthair cat”. The search system converts this query to vectors, and compares it to the index in the vector database. It then returns a given number of articles (the amount is referred to as “k”) semantically closest to your query. The metadata (key-value attributes) of the result contain either the original text or the location it can be found at, such as a URL or an S3 object key.

Next, you retrieve the source data, again either directly from the metadata or from the original location. Finding the right data in an index and retrieving the original text is the “retrieval” part of retrieval-augmented generation. The last part is bringing it all together. Now that we have the original content of the most relevant text, we can insert it into the {context} placeholder of our query template.

SYSTEM MESSAGE: You are a helpful AI which helps the user answer questions about their business data. We will provide the source material as context.

CONTEXT: This is the most relevant business data related to the user's query:

{context}

QUESTION: {question}We insert the user’s question (“what is the average weight of a American Shorthair cat”) about the data in the {question} placeholder, and let the LLM go to work. Again, no retraining required!

Conclusion

In this article we have provided a simple explanation of retrieval-augmented generation (RAG). We covered the limitations of LLMs, how we can use context to provide actual or private data, and how we can use vector databases to find the most relevant data for a user’s query. In practice, there are many nitty-gritty details to indexing, embedding, vector comparison, chunking, prompt engineering, and much more to make RAG work well. We will leave these topics for another post.

We have seen how RAG boils down to retrieving data relevant to the user’s query, feeding it into the the question, and sending the combined context to the LLM to process. This allows LLMs to answer questions about data not included in its training data. The upcoming popularity of RAG also explains the current hype and importance of vector databases. For example, AWS Re:Invent 2023 had at least five vector-related releases:

- AWS announces vector search for Amazon DocumentDB

- AWS announces vector search for Amazon MemoryDB for Redis (Preview)

- Vector engine for Amazon OpenSearch Serverless now generally available

- Amazon OpenSearch Service now supports efficient vector query filters for FAISS

- Amazon Aurora PostgreSQL now supports pgvector v0.5.0 with HNSW indexing

I hope this post helped you understand some current approaches to private data and LLMs. If nothing else, I hope it demystified the term RAG. In the end, it’s nothing more than saying: hey LLM, here is a bunch of data, can you tell me <X> about it?