This morning AWS News had a minor production incident. The platform sends out a daily digest of the most popular AWS news articles, but today, it didn’t. The causes weren’t hard to find or solve – but they did teach me a few things.

As you might know, my side project AWS News collects news from various AWS sources and makes it easy to search and track their articles. About six months ago I added daily, weekly, and monthly email digests. These emails summarize the ten most popular articles, allowing users to quickly catch up with the news. (If you’re interested, sign up here: https://aws-news.com/subscribe)

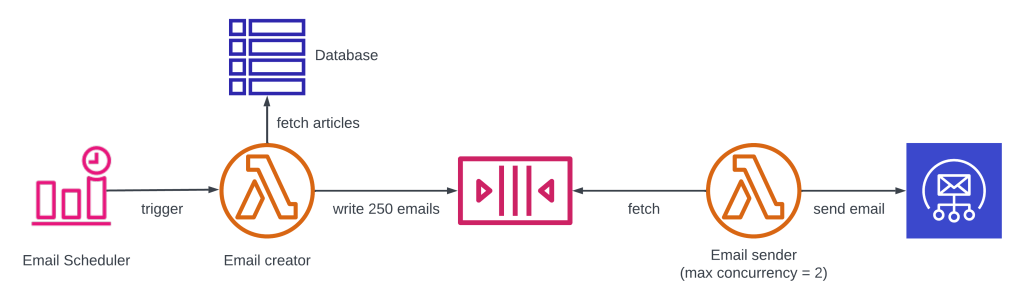

I use Amazon Simple Email Service (SES) to send these emails, but for obvious reasons this service is rate limited. My current quota is 14 emails per second. AWS News sends more than 250 emails at a time, so if I would send all of them to SES at once, it would reject most of them. So I built the simplest rate limiter I could think of, using Simple Queue Service (SQS) and Lambda.

The max concurrency of 2 on the email sender function, combined with the execution time of that function, caps the maximum number of messages to about 150 per minute – well below the 14 per second limit. This system has served me well for about six months.

However, today the system broke. Astute readers will already have realized where this design went wrong: SQS has a message size limit of 256KB, and today the email batch crossed that threshold. SQS rejected all messages, and no email was sent. Not a super complex issue, so the solution was quickly implemented:

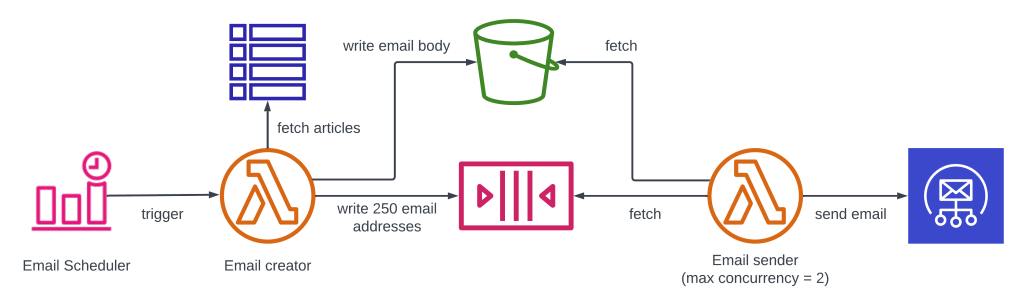

Instead of writing the full email to SQS, the adjusted solution writes the contents to S3, and only sends the email addresses and the object key to SQS. The rate-limited email sender will still trigger for every message on the queue, but will fetch the email body from S3. This is also called the claim check pattern.

All’s well that ends well. But what has this minor incident taught us?

Invest in observability early

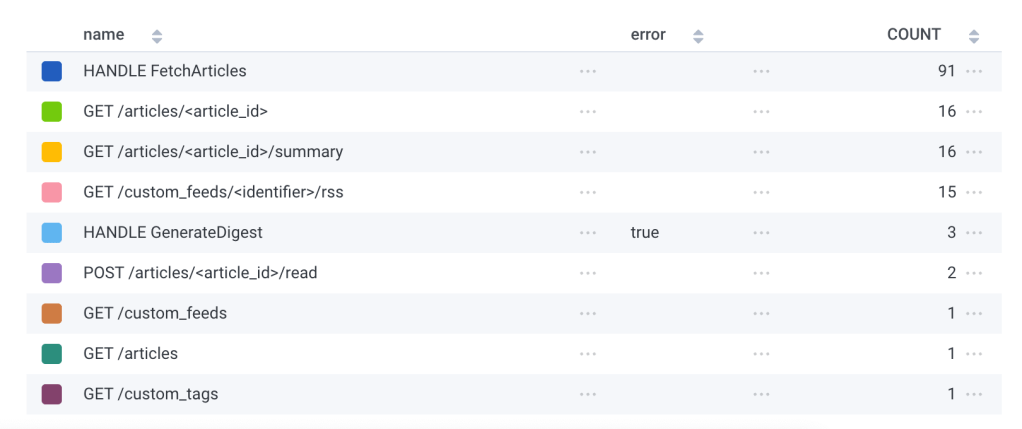

First, the speed with which I could determine and resolve the issue. The total time to recovery was about an hour, and this is mainly due to an extensive observability strategy. When I realized I hadn’t received my daily email, I navigated to my Honeycomb dashboard and immediately saw the table below. (Criticasters will note that this should have been an alarm instead of me noticing a missing email. But this is a side project and I am not going to set up on-call duty for myself.)

Diving into these failed calls showed me the following trace:

The error could not be clearer. Within five minutes I was working on the solution. But of course, I could not have done this if I hadn’t spent hours in an earlier phase, building out the observability tooling and instrumentation to give me these insights.

Software architecture and testing

The new solution involving S3 required some changes to the infrastructure. Changing software and infrastructure always carries some risk, especially when you’re working under the pressures of a production incident (even a minor one). Luckily, I spent a lot of time implementing a scalable software architecture, which strongly separates different use cases, services and entities from each other. This onion architecture makes sure that the changes I made to the email service do not affect other services.

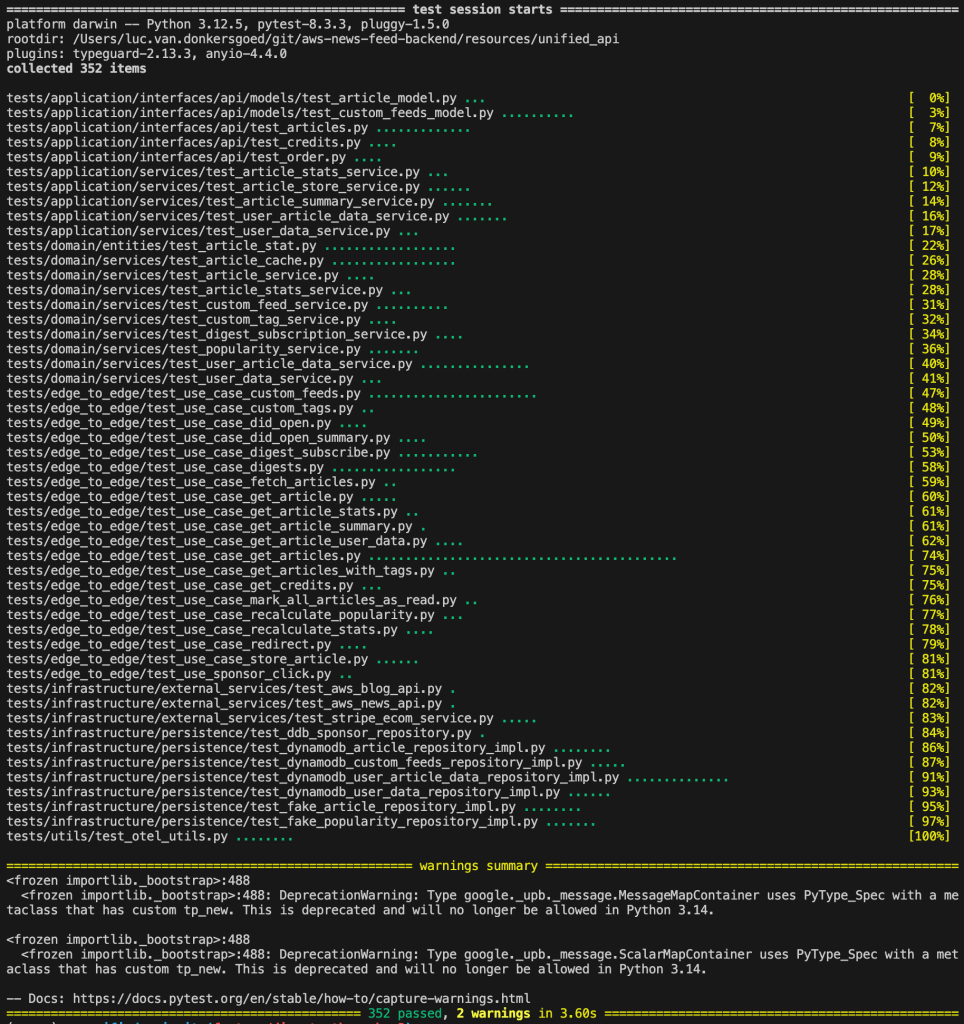

Onion architectures also make it very easy to test applications. This has allowed me to add hundreds of tests over the past months, which give me great confidence in my deployments. In fact, even as I made today’s changes, I added another four tests.

Carried by a rigorously implemented software architecture and hundreds of tests, I could quickly solve today’s problem and rest assured my changes would not affect the rest of my system.

You’re not gonna need it – until you do

When I designed the original SQS solution, I figured my emails and subscribers wouldn’t grow too fast, and a more complex solution was not needed. It certainly wasn’t needed at the time. In other words, I followed the YAGNI principle – you’re not gonna need it.

The flip side of YAGNI, however, is that at some point you might actually need it. In hindsight, I should have considered the tradeoff I was making with SQS and I should have implemented an alarm on the maximum SQS message size. This could have warned me the system was approaching a critical threshold, so the incident could have been avoided.

But then again, this is 1) still a side project, and 2) not all trade-offs are known at design time. Sometimes you just have to accept that incidents will happen, and that the observability and testing solutions will help you resolve them quickly when they do.

Bugs travel in pairs

I think almost everyone responsible for operating infrastructure knows this: an incident is seldomly caused by a single clear bug or error. Almost always, it’s a collision of multiple things going wrong at the same time or amplifying each other. This, combined with the pressures of a production incident, is what can make finding a root cause challenging.

The same happened today. I solved the issue above, deployed everything to my staging environment, and sent out a test email… only to be greeted with another error message. This time the error was a different AWS error: botocore.errorfactory.ValidationException: An error occurred (ValidationException) when calling the InvokeModel operation: Input is too long for requested model.

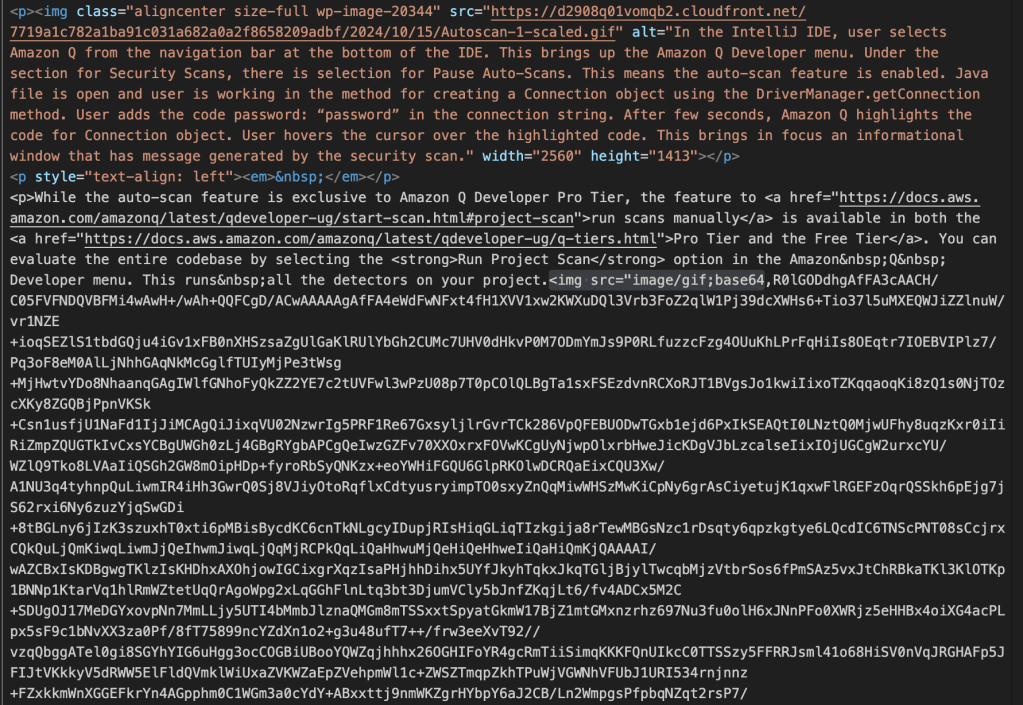

The error occurred in the LLM service (Bedrock / Claude) I use to create summaries. I was baffled, because I had never seen this error before. The context window is supposed to be 200.000 tokens, and the news articles are never this long. But again, my observability solution could tell me exactly which article caused the error. I dived into the news source, and found this:

This one article had an image encoded with base64 embedded right into the source HTML! This made the article more than a megabyte in size, and my service tried to send all of that to Bedrock to summarize… but got rejected. In a way I’m lucky, because this could have been an expensive bug if it went through!

Again, the fix was easy. I now strip all images from the source text before sending it to Claude – the LLM cannot access the images anyway, so nothing is lost. And as an added bonus, I now use even fewer tokens than before this incident.

Data lineage pays off

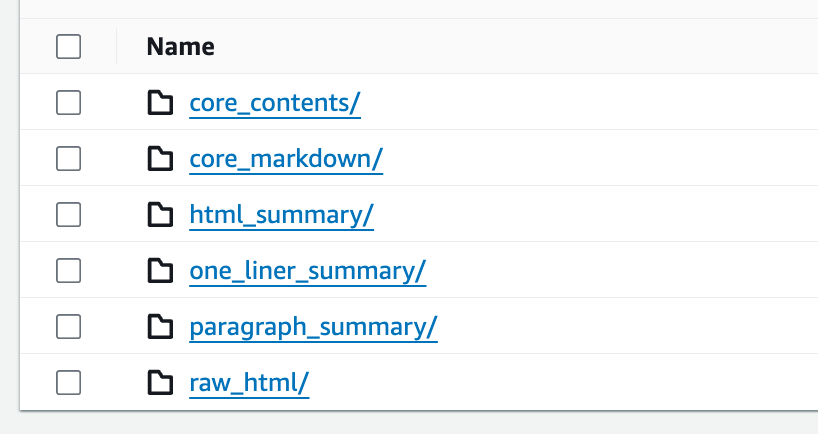

The AWS News platform performs quite a bit of data wrangling on the source articles. It takes the original content, strips all superfluous HTML, converts it both to plain text and markdown, and generates long form and short form summaries. The system stores every intermediate step in S3, which allows me to reuse and inspect their outputs. In the S3 bucket, this looks like this:

Because my observability traces told me exactly which article and source file was the culprit, I could browse to it, download it, and immediately see the unexpectedly large file size. If I would have used ephemeral files (only kept in memory), finding this issue would have been seriously more difficult.

Conclusion

Today’s incident was a minor one. The only negative effect was a slightly delayed email for about 250 subscribers. But as this article shows, even minor incidents can teach you a lot. Maybe even more importantly, this incident proves the value of observability, software architecture, testing, and data lineage. Without them, this incident would have cost hours more to solve.

This fire drill gives me the confidence that if a larger incident occurs in the future, I am well equipped to solve it. Just don’t take this as an invitation, Murphy!