As I’m typing this, Re:Invent 2024 is only weeks away. In anticipation of https://aws-news.com‘s busiest period of the year, I redesigned the API access patterns to support very effective caching. This resulted in significantly reduced backend load and a much faster frontend.

This article focuses on CDN caching – storing HTTP responses on points-of-presence (POPs) near the user. When you read ‘caching’ in this article, we’re talking about caching in CloudFront, unless stated otherwise.

Background

My strong suit is backend development in Python on AWS. Conversely, I’m quite lacking in frontend and Typescript skills (although they’re getting better). So when I started building AWS News I naturally composed most of the business logic in the backend. This included enrichment features, such as mark as read, bookmark, and rating of articles. As a result, retrieving articles from the backend always yielded a personalized response. In this article we’ll learn why this approach does not promote efficient caching, and what the better alternatives are.

The three components of an article

An article on AWS News has three types of data:

- Data related to the article itself, such as the title, URL, and publication date

- Data related to the article’s presence on https://aws-news.com, such as its popularity and read counts

- Data related to the user reading the article, such as its mark-as-read state, bookmark state, or user tags applied to the article

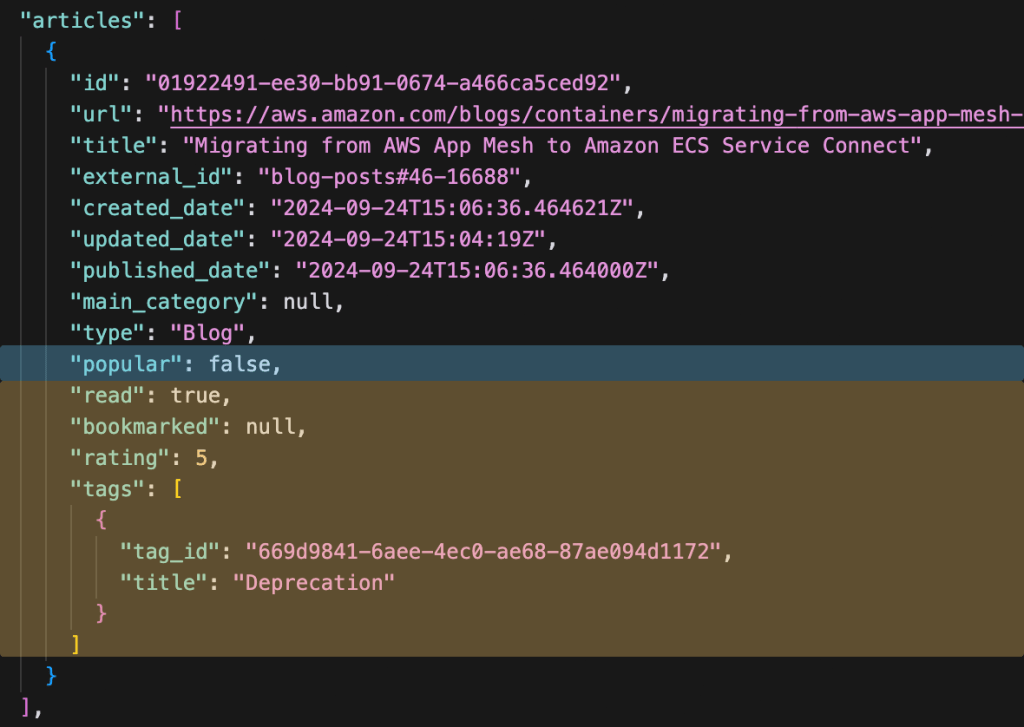

In the first iteration of the AWS News API, a GET /articles response looked like this:

Notice how we’re combining the three types of data? Since this response contained personalized data, it was impossible to cache efficiently. Maybe the response could be cached for repeat visits by a single user, but as soon as the user data or popularity of the article changed, the cache would need to be invalidated. In practice, I did not cache these responses at all. Efficiency and cost aside, this meant the user generally had to wait for 300-700ms for the different data sources to be retrieved, combined, and sent over the wire. For every request. Not a great user experience.

Classifying data by cacheability

To improve the efficiency of AWS News I looked at the data returned by the API and classified it by cacheability. This led to the following categories, ordered from least dynamic to most dynamic:

- Data which only changes when new articles are added or updated in the database: long-term caching

- Data which changes periodically, for example every 10 minutes or every hour: short-term caching

- Data which might change with every request or is different for every user: no caching

Pro tip: do not mix data with different lifecycles in a single HTTP response. It will limit the cacheability of the response to the lifecycle of the most dynamic value.

With these lifecycle categories identified, the problem with the initial design became clear: because the response contained values with different lifecycles, including always-changing data, the entire response could not be cached.

Introducing new endpoints

To solve this problem, I had to change existing API endpoints and introduce new ones: the endpoint for articles had to be stripped of dynamic data, and the endpoints for popular articles and user data had to be hosted under their own paths. The new urls became:

GET /articlesGET /articles/popularGET /articles/user_data?article_ids=....

With the user data and popularity removed the GET /articles call clearly falls in the long-term caching category. A response on this endpoint now looks like this:

This data will not change as long as the article data in the database is not updated. In the example above we’re only looking at a single article, but search results, lists, pages, and summaries all fall in the same category. After all, a GET /articles?search=Lambda will always yield the same results, as long as the contents of the article database do not change.

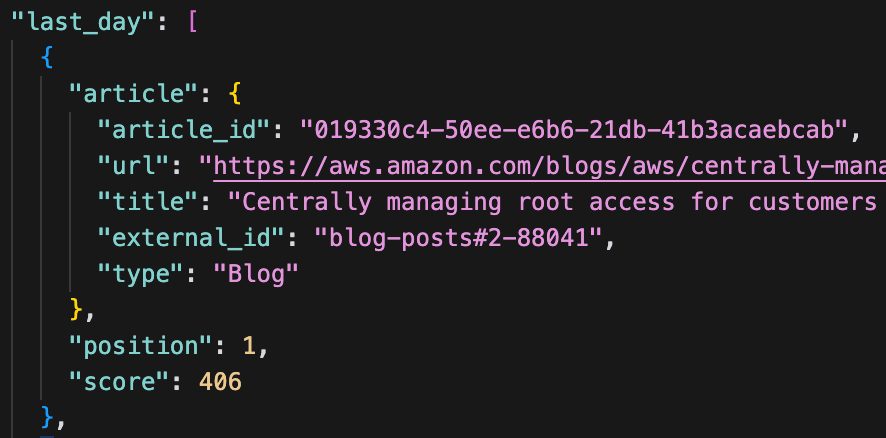

Popularity data falls in the second category – it changes periodically. For example, a GET /articles/popular response looks like this:

The popularity data is based on user interaction with the site, and is recalculated every 10 minutes. Within this window of 10 minutes the response will never change, making it a good candidate for short-term caching.

The third endpoint is new, and was specifically added to support better caching of the first endpoint (GET /articles). The new GET /articles/user_data?article_ids=... endpoint allows the frontend to asynchronously fetch the user data for the articles displayed. By splitting these calls every user can fetch the cached articles extremely quickly, after which logged-in users will have their articles enriched with their personal data. The response of the user data call looks like this, and will never be cached:

By separating the data with three different lifecycles into three different endpoints, the system can start caching each of them with their own ideal time-to-live (TTL).

Increased frontend responsibility

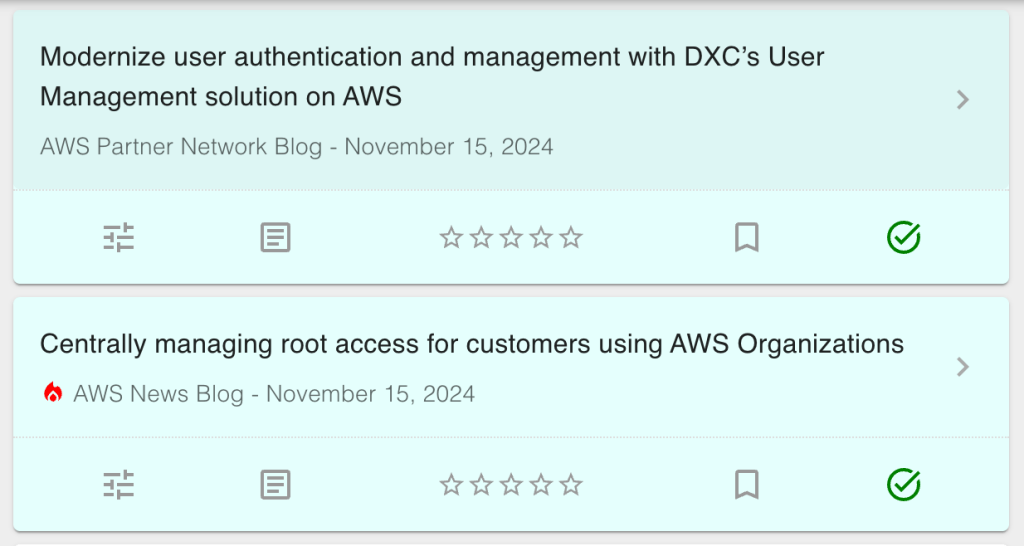

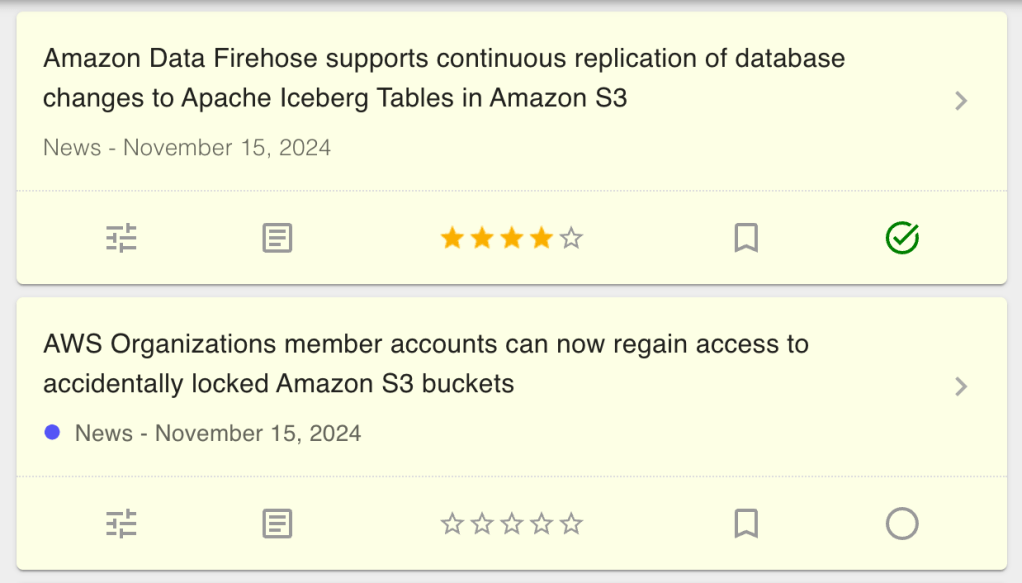

The flip side of this approach is that the frontend gains new responsibilities. Back when all data was returned in a single request, the frontend could just display the results as they came in. With the separated calls, the frontend first needs to fetch the articles and the popularity data (this can be done in parallel). When the articles have been retrieved, the article lists can be displayed. If the popularity request finishes after the articles request, the article cells will need to be updated with a ‘hot’ icon where applicable.

After the articles have been loaded, the frontend needs to do an additional request for the user data. When this data has been retrieved, the read, bookmark, rating and tags icons need to be updated.

I found building this in React / Next.js quite challenging. I had to use hooks, stores, contexts, effects, and a lot of other dark magic to make it work. Especially preventing reloads and unnecessary rerenders cost me many hours. But! It works and I’m happy with the results.

Results

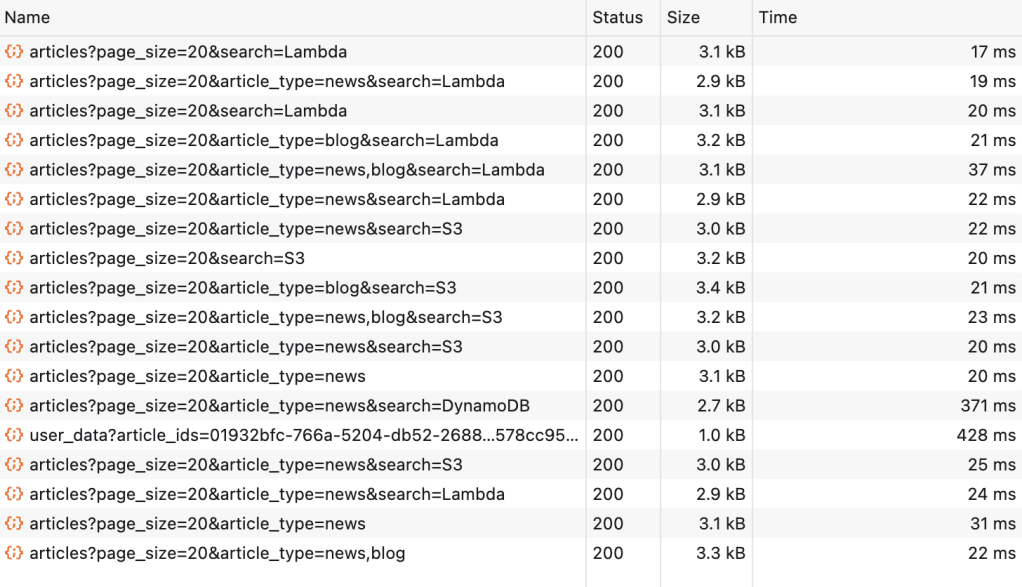

Speaking of results, let’s take a look at the speed at which the AWS News frontend now retrieves data. Here’s a view on the network requests as I’m clicking around on the site, filtering blogs and news articles, and searching for various terms.

As you can see, most requests are INSANELY fast. Out of 18 requests, 16 hit the CDN cache. Out of these 16 requests, 14 completed under 30ms. You can also see one GET articles request not hitting the CDN. This was a search for DynamoDB, which had not been performed since the last cache invalidation. At 371ms, the request still completed quickly enough, and any other user searching for the same term would now get the response from the cache. You can also see the user_data request, which takes a little longer – but that’s okay, because the user could already scroll through the articles as soon as the GET /articles call finished.

But these are just numbers. What does 30ms actually look like? Here’s a video.

It’s fast. And that’s not the only win, because this approach also greatly reduces the number of backend invocations. This means fewer Lambda calls, fewer S3 retrievals, fewer database calls, and generally lower cost.

Cache Invalidation

There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.

We’ve seen that our new caching strategy has delivered great response times. And this makes sense: if the data doesn’t change, we don’t calculate it and we host it close to our users. But what if the data does change? The way I see it, there are two approaches you can take:

- Create a comprehensive cache invalidation mechanism and spend days making sure the right objects are invalidated at the right time.

- Nuke the cache when something changes.

I chose the latter. At the scale of AWS News, cache misses and the resulting recalculations of responses aren’t terribly expensive. So whenever an article is updated or newly added to the database, I just create a /* invalidation, removing all cached objects from the CDN. This guarantees that every page, every search query, and every list includes the updated values. It also means some data which hasn’t changed will be invalidated and will need to be retrieved again, but I found this an acceptable trade-off.

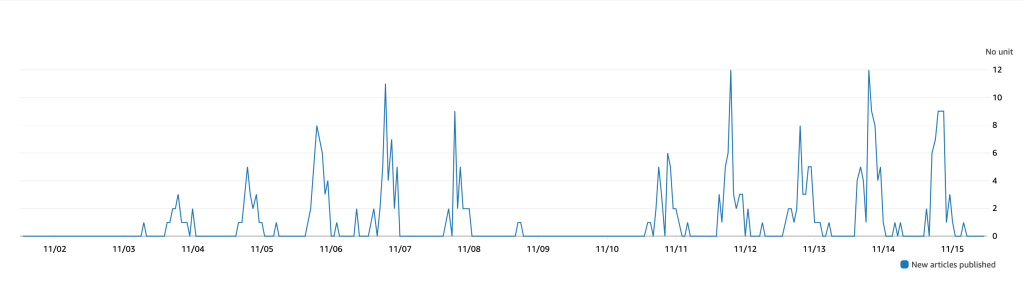

An additional argument for nuking the cache is that the articles database doesn’t actually change too often. Generally, AWS releases news and blogs five days a week, between 10AM and 4PM Seattle time. During these periods the cache will be invalidated a few times, but outside these periods the cache is stable for many hours, sometimes even days.

Invalidation debouncing

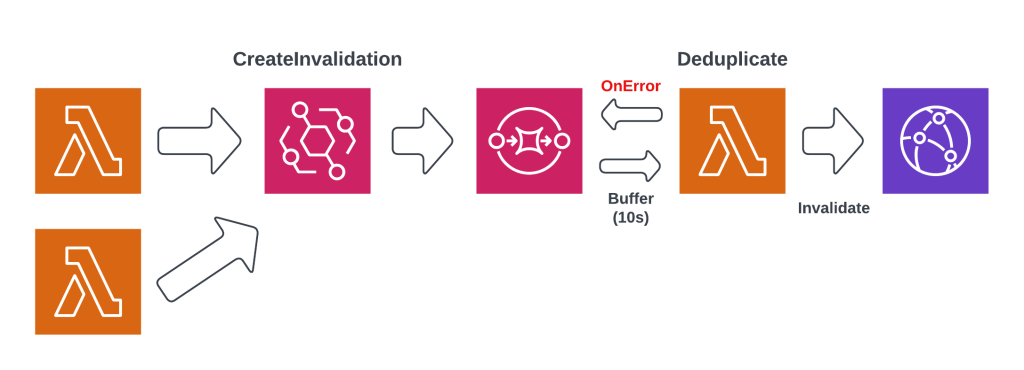

Nuking the cache every time an article is created or updated had an unexpected side effect. Sometimes AWS will release a number of articles at the same time, leading to multiple invalidations at the same moment. Additionally, some parts of the backend system might create multiple invalidations for the same article. This can lead to rate-limit exceptions in CloudFront, as well as some cost. To solve these problems, I created a invalidation debouncer using SQS and Lambda. Instead of directly invalidating the CDN, my backend system now write an CreateInvalidation command to SQS. The SQS queue has a batch window of 10 seconds, which means it collects events for 10 seconds before sending them as a batch to Lambda. The Lambda function filters out any duplicates and only invalidates the CDN once per invalidation pattern. If any of these invalidations fail (maybe they are still being throttled), the message is returned to SQS and retried 30 seconds later. This guarantees that requested invalidations are always executed, which is essential for surfacing new articles in the frontend (almost) as soon as they are published.

The diagram above shows the debouncer design. This solution makes it very easy to trigger invalidations from any corner of the system, while buffering, deduplication, and retry logic is completely handled by the debouncer system.

UX mitigations

One effect of splitting the single GET /articles request into three separate calls is that the UI can no longer be rendered in one pass. Instead, the layout is updated as each of the responses come in. Initially this led to a very twitchy design, with UI elements suddenly changing as the data changed. An example can be seen below.

To solve this, I added some ease-in animations to the the UI. The data is exactly the same, but by smoothly transitioning into the new state the change is a lot less jarring. I expected this to be one of the more challenging parts, but CSS animations are really quite simple to implement!

Conclusion

At its core, this article is about trade-offs. Initially I chose to minimize frontend logic to optimize time to market, but as trade-off I got an uncacheable design. Then I optimized my API for caching, leading to much, much faster response times and initial renders, but at the cost of additional complexity in the frontend. It also added new cache invalidation requirements to the system, which required additional moving parts like the invalidation debouncer. Finally, the asynchronously loading UI is much faster, but required additional UX work to make it visually acceptable.

Regardless of the additional complexity, I advice everyone to consider the lifecycles of the individual fields in their HTTP responses. If you discover mixed lifecycles in the same response, you may have identified a design flaw in your API. Separating them into different calls will introduce some additional complexity, but in the long run it will make your applications much more scalable and maintainable.

As you were reading this post, you may have seen other potential improvements. For example, user data can also be cached. Database queries can be cached. We can use smarter invalidation strategies. All of this is true, and if I have the time and need to implement them I’ll be sure to write a blog post about it.