One of the most interesting aspects about software is that it is never done, and it is almost impossible to predict what it will look like even a year later. I find designing for evolution a fascinating challenge. In this article I will share how we recently used onion architecture to deal with uncertainty, and how a small investment in design yielded big payoffs only weeks later.

We will cover two fundamental concepts: separation of concerns and cohesion. We will show how we applied these concepts within the onion architecture framework, and how together they helped us evolve an application quickly. By the end of the article you will have learned:

- How fundamental concepts like separation of concerns keep your software maintainable.

- How software patterns like onion architectures help you automatically apply these fundamental principles.

- How some concepts, like cohesion, can also be applied wrongly – which effectively makes your software less maintainable.

- How refactoring allows you to recover from mistakes, and how a robust software architecture makes refactoring a breeze.

In my previous article “Are humans the limiting factor in AI-assisted software development?” I state that code is written for humans. The concepts covered in this article support that premise: modularity, low coupling, separation of concerns, abstraction, and cohesion help us humans understand and maintain the code, which leads to better software in production. The application described today was definitely not the result of vibe coding, but we weren’t AI Luddites either – we used Cursor, ChatGPT, and CoPilot extensively to support our craft.

The project

In this blog post we’ll cover an initiative to deliver a greenfield application in five months. Five months to go from nothing to a fully featured, high-volume, mission-critical application. The project’s goal was to build an integration platform which handles about 80 million requests per day. The platform should be able to receive messages in different formats (JSON / XML / CSV / …), over different protocols (HTTPS / S3 / SQS / …), apply validations, transformations, conversions, and filters on them, and propagate the converted messages in other formats and protocols to consumers.

The challenge

The five-month period was a given – the end date of the project was Friday February 28th. After that another team would take over ownership and further development. The goal was to deliver the broadest set of features and the most robust software architecture for our successors. Additionally, we knew that the integrations we had to onboard would have unexpected, unexplained, and downright weird requirements. This created a context of high unpredictability – further strengthening the need to quickly learn, pivot, and evolve.

Investing in software architecture

We settled on a number of foundational principles early. These included the use of onion architecture, dependency injection, and ports and adapters. We knew that these concepts would help us structure our code in predictable, maintainable, and evolvable ways. However, structuring the application for these principles takes some time – and more than a little debate! You have to agree on libraries to use, naming conventions, folder structure, and some tooling. And you can’t design everything up front. Some decisions need to be experienced before you know if they work, and whether they should be kept or taken out.

One could argue this approach slowed us down. We could have used the days spent on design, debate, and scaffolding on writing business logic instead! And indeed, functionally, our code could have been a single 50,000 line file. But we knew this would hurt us in the long run. And as you’ll read below, we turned out to be right.

A good design decision

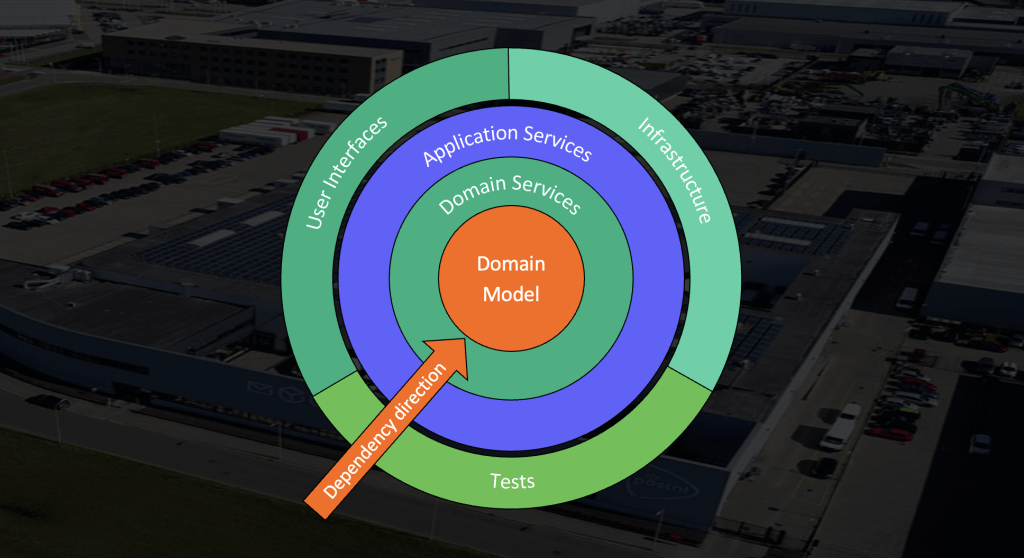

We chose to use onion architecture as the foundational software design for our application. There are many interpretations and significant details about onion architecture, and not all of them are relevant for this story. However, we do need to cover some core concepts.

First, the layers of the onion. In the center we see the domain model. This contains business entities which can be used throughout the application. Since the application we’re building is an integration platform, this layer is very small. The layer above that contains the domain services. These perform standalone business logic, such as “convert an XML to JSON”, “transform an XML object according to the given mapping template”, “validate a JSON file using a JSON schema”, and so on. The third layer is the application services layer. These services orchestrate the domain services, for example by making sure a JSON is first validated with a schema, then converted to XML, then transformed, and then forwarded to a consumer. If any errors occur during this process, the application service handles the failure. When the operation is completed, the application service reports the result to its caller.

The important details to remember are that:

- Domain services perform business logic, but they never know the context in which they are being executed. They just perform an operation with the provided parameters on the provided input, and return a result without any side-effects.

- Application services never contain business logic. Instead they only orchestrate; they call domain service operations, check if they were successful, and decide the rest of the execution path based on the results.

- The dependency direction is inward, which means application services can import and call domain services, but never the other way around. This enforces the strict separation of rule 1 and 2.

The adept reader will have realized this is separation of concerns in practice. Since our application is an ephemeral data pipeline, our heuristic is whether an operation reads, writes, or mutates the data in-memory data. If it does, it belongs in the domain services. If the operation only relates to the flow of data, not the data itself, it belongs with the application services. By applying this simple rule we strongly separated the concerns of orchestration and business logic.

A bad design decision

At some point in our development process the orchestration process posed an interesting challenge. We expected to onboard around 80 integration flows, and each of those had its own unique configuration. Some converted JSON to XML, some converted XML to JSON, others received XML, transformed it, and forwarded XML again. To specify how the application should behave for a given flow, we designed a configuration language in YAML. This language was very straightforward, for example:

---

Actions:

- ExtractJSONFromEnvelope

- ValidateJSON

- ConvertJSONtoXML

- ValidateXML

- ForwardToS3

The application services needed to dynamically convert these instructions to domain service operations. We looked at the list of potential operations and realized they always followed an Extract / Transform / Load (ETL) pattern: first we pre-process the data (extract), then we transform the data, and finally we forward the data to a destination (load). After seeing this we separated the actions themselves into three different modules, creatively named the ExtractUseCase, TransformUseCase, and LoadUseCase. We achieved temporal cohesion by putting the processes executed in the same phase in the same place. We were happy and continued our software development journey.

Running into trouble

However, one or two weeks later, this approach started to “smell”. We found that our orchestration layer had an increasing number of conditional statements: if the result of a domain service operation is a boolean, do X. If it is a list, do Y. If the result is of type FilterResult, check if is_filtered is true, then do Z. The complexity of our code exploded, and we didn’t really know what caused it. We held multiple design sessions to find a solution, but to no avail. I personally spent at least two nights till midnight banging my head at this problem, but nothing worked. Until it hit us: we used the wrong type of cohesion.

When we chose to group our actions into ETL modules we didn’t realize that within each of these modules – especially the Transform module – the action interfaces varied wildly. Some accepted a data object and returned a boolean. Others accepted a list and returned a single object. Some accepted an object and potentially returned nothing. We accidentally grouped very different objects and pretended they were the same. We thought we neatly organized our modules, but we created three “everything drawers” instead.

Refactoring the mistake

When we realized what went wrong, the solution was quite simple. Instead of categorizing our actions by their place in the ETL lifecycle, we grouped them by interface. We came up with the following categories:

- Validators: data object in, potentially returns a validation error

- Transformers: data object in, data object out

- Filters: data object, filter result out

- Splitters: data object in, multiple data objects out

- Forwarders: data object in, forward result out

With this design the actions in the same category shared the same behavior and interfaces – this time they were functionally cohesive. This allowed us to greatly simplify our orchestration code and remove the code smell introduced by our unintended complexity. The core orchestration code – which used to be a mess – ended up looking like this:

But the biggest win was the ease with which we were able to apply this refactor. Remember that the business logic entirely lives in the domain services layer. The problem we faced and solved occurred only in the application services layer. Because we strictly adhered to the principles of onion architecture, we saw no code change outside the affected files. In other words, there was low coupling between layers, and our application did not suffer from change amplification. These results show our software architecture achieved the goals we designed it for.

Conclusion

Software development is a profession unique in its unpredictability. Business requirements change, macro-economic factors change, and technologies and tools change fastest of all. These changes each affect an application under active development. And in today’s example our own insights changed even as we were writing the application. To cope with this uncertainty every non-trivial application should be designed with evolvability in mind. Luckily, there are ample tools and patterns to help us achieve this.

In this article we explored the value of investing in an opinionated software architecture with strong guardrails. We saw how it forced us to separate concerns according to a predefined design, and how this structure and consistency helped us refactor with minimal side-effects. We also saw that it’s natural to make mistakes or take a wrong turn every now and then. I would even say it’s inevitable. This is fine, as long as you’re able to register your mistakes and spend the necessary effort to correct them. If you follow these guidelines, your applications will remain maintainable and evolvable well into the future.

Credits and further reading

Thanks go out to my PostNL colleague Stefan Todorov, who first shaped my thoughts on onion architectures and the responsibilities of each layer. The fundamental methods and principles in this article were further influenced by two books:

- Modern Software Engineering: Doing What Works to Build Better Software Faster, by David Farley

- A Philosophy of Software Design, by John Ousterhout

I consider both must-reads for anyone with a serious interest in software craftsmanship.